A few weeks ago, one of my dearest friends, who is now the editor of a paper in Limerick, Ireland, asked me to write a piece about fertility treatment and adoption in Ireland. My friend Rachael knows the ins and outs of why we moved to Houston – she and her husband even visited us this time last year, when had baby J (number 2). We met when we both thought we were food bloggers – many years ago now – and now that we’ve both realized we’re actually writers (and in her case, an editor!) we’ve remained close friends despite 4,000 miles between us.

A few weeks ago, one of my dearest friends, who is now the editor of a paper in Limerick, Ireland, asked me to write a piece about fertility treatment and adoption in Ireland. My friend Rachael knows the ins and outs of why we moved to Houston – she and her husband even visited us this time last year, when had baby J (number 2). We met when we both thought we were food bloggers – many years ago now – and now that we’ve both realized we’re actually writers (and in her case, an editor!) we’ve remained close friends despite 4,000 miles between us.

So Rachael emailed because she had a feeling the article would be up my alley, and of course it was. It was the entirety of why we moved to Houston, in 1800 words. It was particularly timely because the Irish government had just announced plans to cover fertility treatment for couples (along with outlawing commercial surrogacy and regulating the heck out of embryo and sperm donation) starting in 2019. It gave me an opportunity to talk about a subject that isn’t just near and dear to me, it shaped the entire trajectory of my life.

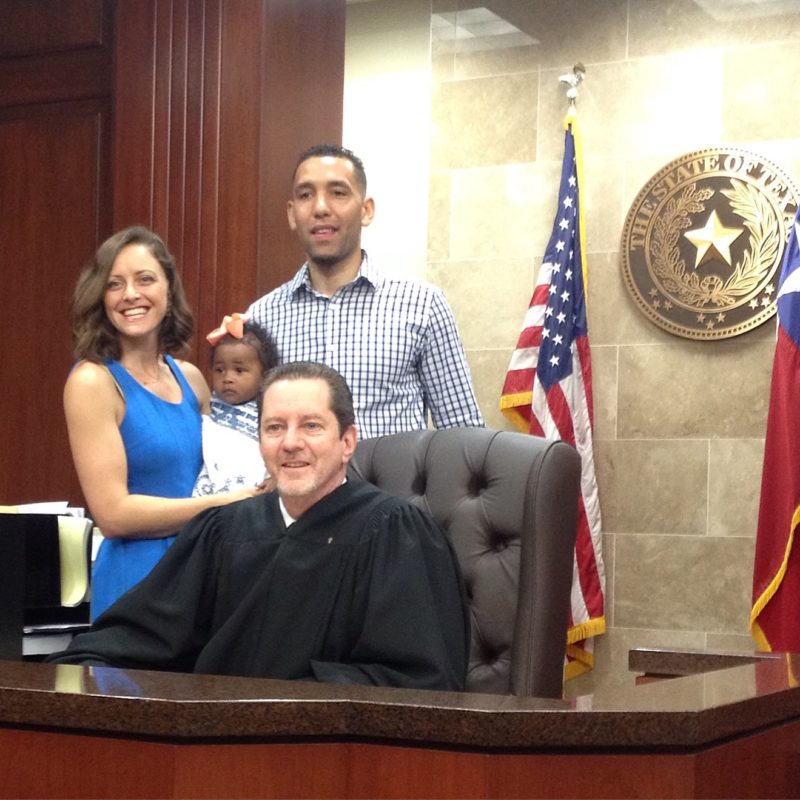

A few years ago, actually the night before we got the call that Maya was going to be joining our family, I shared why we were still lingering in Houston. It was a hard announcement for Michael and I to make because our lives were really and truly built in Dublin after almost 8 years of living there. I think it was even a little hard for us to accept ourselves, until I wrote the words on my blog. Not 24 hours later, Maya was in our arms.

We moved to Houston because we weren’t interested at the time in undergoing expensive fertility treatment and we had always wanted to adopt. Adoption was and still is functionally impossible in Ireland. Domestic adoption in Ireland is all but nonexistent – even through foster care (24 children were adopted from foster care in 2015, and there were 7 domestic straight adoptions in the same year). When I initially explained why we moved to Houston, I linked to an article in the Irish Times about the state of adoption in Ireland, but I didn’t go into much detail about the state of adoption in Ireland. Well, have a look at this more recent Irish Times article and know that very little, if anything, has changed in the last seven years. If the headline, “Changes to adoption law have shattered my hopes of becoming a parent,” doesn’t break your heart, I don’t know what would.

The lack of domestic adoption opportunities seems, on the surface, like a good problem to have. Babies aren’t given up for adoption, that must be positive, right? Everyone has a happy home! Yay! Well, I think it’s more complicated than that. Because of the Irish constitution, parental rights are rarely terminated in Ireland. Instead, children can spend their entire lives in foster care if their parents aren’t in a position to parent them. We have friends who foster in Ireland and while they expected to have their foster daughter in their home for a few months, she has been there for over a year and they don’t expect she is likely to ever be reunited with her biological parents. Yet it is more likely that she stays in foster care for many years than be adopted. I feel strongly that extended foster care is not a better option than adoption for a child, especially because the likelihood that a family could foster a child indefinitely isn’t that high; basic everyday parenting decisions pertaining to medical treatment, vaccination, travel, school registration and the like require state intervention and approval. And even if foster parents could foster forever, it deprives foster children of the security and stability of a formal adoption.

Among my complaints about the Catholic church in Ireland, the treatment of unwed mothers that has greatly influenced this current state of foster-care-forever is high on the list. In the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s, the children who were born to unwed mothers living in Magdalene Laundries were often sent (without the consent of the mother, obviously) to the United States to be adopted. Many of them never knew where they ended up, a lifetime later. My friend Sharon, the producer of Adoption Stories in Ireland, helps some of them reunite with their long lost children, but that is only a drop in the bucket. If there were 800 babies in the mass grave at the mother and baby home in Tuam, there are thousands who were wrongfully taken from their mothers and shipped away.

Giving your child up for adoption isn’t exactly glorified in the United States, but I think it’s more accepted and more understood. In Ireland, it’s more shameful to give up your child than to have your parents raise it and have it end up in a group home as a teenager because he or she is too difficult for an elderly person to take care of. The pendulum has truly swung against domestic adoption in Ireland, to the point where it’s essentially nonexistent.

Meanwhile, international adoption is a process that involves a 3+ year vetting by the Irish government before you can even start the international adoption process. During that time they will pore over five years of your medical records (you must have a BMI of under 30), visit your house, your friends and your family, review your household expenditure (down to the money you spend on gas), interview you on the finer, personal details of your private life with your partner and take you through weeks of pre-adoption courses. You have to have stopped fertility treatment for a certain period of time before applying (and have to agree to have your fertility records available to the adoption authority) and none of your children can be younger than nine months when you’re approved to begin the process. Your youngest child has to be two by the time you actually have a child placed in your home – and the kicker is that it will most likely be a child, not an infant.

Despite how excruciating that sounds, every year, hundreds of couples in Ireland present themselves as prospective parents, engaging in a costly, time-consuming and emotionally draining ordeal to prove themselves capable, safe and suitable to care for these children. And yet, the annual number of international adoptions can be counted in double digits. There are actually 80% less international adoptions in Ireland now than a decade ago.

Ten of the 11 countries from which you can adopt into Ireland, placing countries as they’re called, only place toddlers or children, nearly all of whom have been in orphanages for years. They all have additional needs, whether they be medical or psychological. The only program that regularly places kids as young as toddlers is China, which places typically medically affected toddlers no younger than 18 months. There are toddlers in other programmes, but very few, compared to many older, sicker children. The only ‘sending country’ that allows infants to be adopted to Ireland is the United States. Typically, Irish couples who pursue this route will pay between €80 – 90,000 for the process and have to move to America for 12 weeks while the paperwork is completed.

I believe in parenting children from hard places; both of our children came to us with medical risks we were willing to take on and an enormous lack of information that we may wonder about twenty years from now. But I also believe that not everyone who faces infertility can possibly be suited to giving what a child who has lived in an orphanage for years will need. And that’s assuming the child is healthy physically; many of the children placed in international adoption have medical challenges that range from cleft palates and lips to albinism to congenital heart disease, on top of the trauma of living in an orphanage. With the adoption program in China, you have 72 hours to decide whether the child who has been chosen for you has medical needs you think you can handle, knowing full well that the child you meet months down the road will likely have more serious medical needs than you were even informed.

I’ve never once questioned our decision to move to Houston, but delving deeper into the Irish adoption system has certainly made me more confident it was the right decision for our family. It has not been an easy journey, despite the fact that Maya came quickly and both she and Noah are an absolute dream. It has been difficult financially and it has been hard not to have family nearby to give us a break every so often. But while it has been hard to move to a different country to start and build our family, I’ve never questioned our decision, and I’ve always been grateful that we had the option and the opportunity.

Sometimes I question our decision to return to Ireland next summer, but I have a building feeling that I am returning for a specific purpose. What if my role is to shape or shift the adoption and fostering process in Ireland such that it allows for another avenue for family-building? What if being a pushy (or at least thoughtfully outspoken) American might be an asset? I suppose only time can tell whether that is an asset at all!

In any case, it’s a subject I’m passionate about and am hoping to work on when we return next summer. No system is perfect, but it seems like there’s at least a little room for streamlining processes in Ireland that would make a big difference to a lot of families and potential families. I’ll be sure to keep you posted along the way.

In the middle of our trip to LA last week, we took a few days to drive up to Santa Barbara to visit friends. One is a friend from college and her husband and little boy, and the other is my friend Ashley whom I’ve known for years from when we were both ex-pats. I was in Dublin when she was in Berlin and we used to travel to blogging conferences and with our friend Anne. She drove down from San Luis Obispo and spent the afternoon with us at the loveliest, most kid-friendly beachside restaurant/sand box while Maya played and Noah mostly slept.

In the middle of our trip to LA last week, we took a few days to drive up to Santa Barbara to visit friends. One is a friend from college and her husband and little boy, and the other is my friend Ashley whom I’ve known for years from when we were both ex-pats. I was in Dublin when she was in Berlin and we used to travel to blogging conferences and with our friend Anne. She drove down from San Luis Obispo and spent the afternoon with us at the loveliest, most kid-friendly beachside restaurant/sand box while Maya played and Noah mostly slept.

It was so fun to have a reunion on another continent!

It was so fun to have a reunion on another continent!

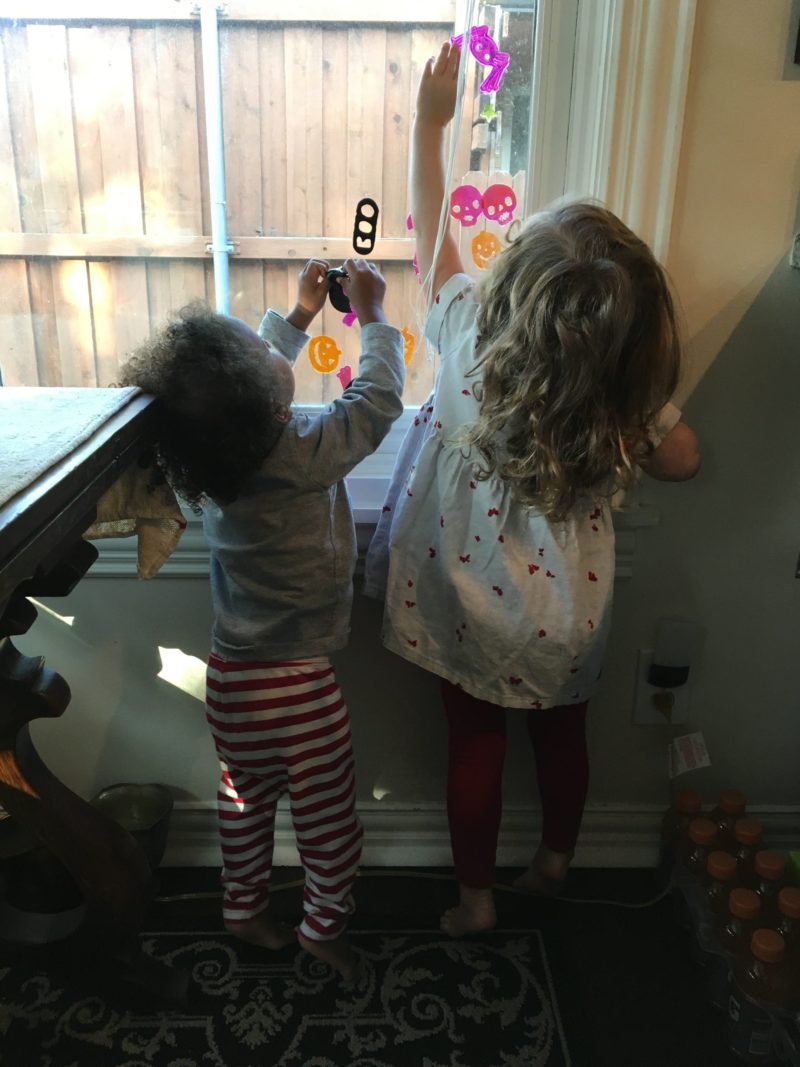

Happy, happy girl.

Happy, happy girl.

There was also a perfectly positioned pool. And warm enough weather to spend some time at least in the hot tub portion of it.

There was also a perfectly positioned pool. And warm enough weather to spend some time at least in the hot tub portion of it.

Even Noah got in on the lounging.

Even Noah got in on the lounging.

There was an outrageous amount of cuteness with the two tiny ones. Can you even?

There was an outrageous amount of cuteness with the two tiny ones. Can you even?

One night, we all went out for pizza in downtown Santa Barbara, and I still crack up over this photo of Michael and Randine wrangling their respective toddlers. How things have changed in 11 years since we were all in college!

One night, we all went out for pizza in downtown Santa Barbara, and I still crack up over this photo of Michael and Randine wrangling their respective toddlers. How things have changed in 11 years since we were all in college!

The light at sunset was incredible up on the mountain.

The light at sunset was incredible up on the mountain.

And some gratuitous photos of the avocados (or as Maya calls them, adocado-cados) and citrus trees because that is the dream, isn’t it? Picking limes from the front yard for margaritas by the pool. Yikes, what a wonderful visit!

And some gratuitous photos of the avocados (or as Maya calls them, adocado-cados) and citrus trees because that is the dream, isn’t it? Picking limes from the front yard for margaritas by the pool. Yikes, what a wonderful visit!

Earlier today I described our trip to LA as exhaustingly refreshing, and it was. It was more work with two kids away from home, but it was also very restorative during the days, to be with friends and family without work obligations or real life chores.

Earlier today I described our trip to LA as exhaustingly refreshing, and it was. It was more work with two kids away from home, but it was also very restorative during the days, to be with friends and family without work obligations or real life chores.